Brazilian History: The Power of Go Betweens

https://phistars.blogspot.com/2012/12/brazilian-history-power-of-go-betweens.html

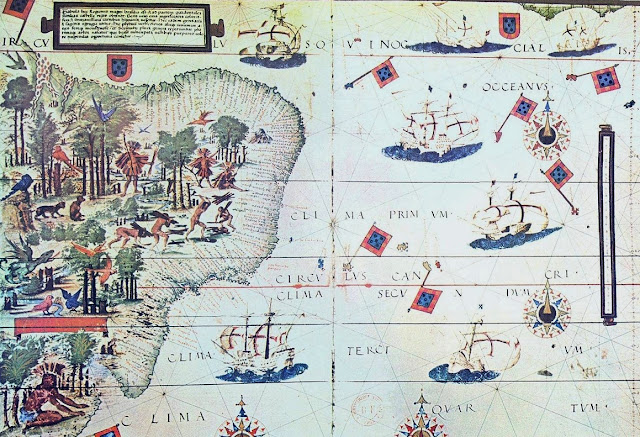

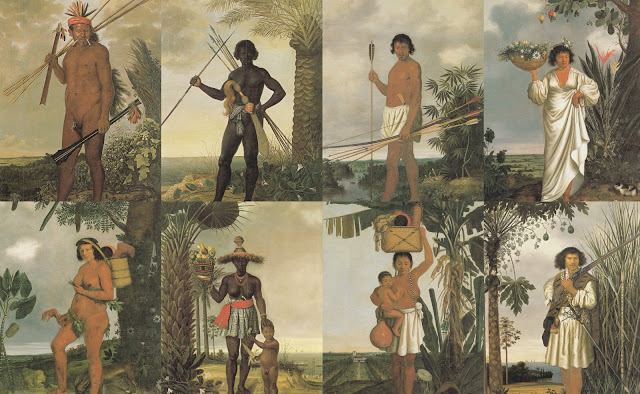

Editor's Note: Sometime has passed, thus, I decided to post my homework on my blog. You know, for pharmaceutical purposes. It was a good essay. It got an A plus. Thus, even my teacher thought my homework was 5 stars worthy. Oh, I am going add a few pictures that relate to my essay. You know, something help you visualize what I am talking about.

Brazilian History: The

Power of Go Betweens

In Colonial Brazil, there was a power struggle between Jesuits

and the Colonist. Each had their own methods of handling the Indians. The Jesuits wanted to keep the Indians in

missions. There they lived relative autonomous life under the guiding hand of

the church. The colonist simply wanted to enslave the Indians. They did not

care much for the Evangelization of the Indians. All that mattered to the

colonist was the increasing revenues.

Well, both methods required go betweens that negotiated

with the Indians. The Jesuits needed them for convincing the Indians to enter

missions. The colonist used them go betweens in order to use other Indians to

collect the slaves for them. In both cases, it was the go betweens that

benefited from the rivalry between the Church and the colonist. For this

reason, the go betweens where seen as a necessary evil. Their ambiguous lifestyle made them a treat to

the institutions of Portuguese society and the Evangelization missions of the

Catholic Church.

In the readings of Metcalf, there appear two types of go

betweens. Dominges Fernandes Nobre or Tomacauna was a go between the colonists

and the Indians[i].

The Lisbon Inquisitor that was sent by the Portuguese crown was a go between

the colonist and the Catholic Church[ii]. Each had their own agenda. Thus, the actions

of Tomacuana benefited the colonist sugar planters. Meanwhile, the Inquisitor

favored the Evangelist mission of the Jesuits and the church. Thus, each was

advancing a different model of colonization.

The sugar planter’s model of colonization consisted on

slave driven labor. Little attention was paid to the Evangelization of the

slave labor. The Amerindian Indians was the closet source of man power. The

Jesuits had managed to make illegal the enslavement of Indians. Still, it was

noted that those regulations where rarely enforced[iii].

Plus, many Indian slaves did not survive their captivity. Thus, their

population was seriously dropping.

The model of the church model of colonization focused on

missions. Basically, the Jesuits or other priestly ordered created a town of

Indians. In this town, the Indians worked for the priest. Aside from work, the

Indians obtained education in both Catholics and European practices. Via this

method, the Indians where slowly integrated into the Portuguese society.

Integration did not benefit the planters. The time spent learning was a time

the Indians did not spend working. Thus, to evangelize it became necessary to

keep the Indians away from the regular sugar planters. This separation was also meant to keep the

pure from the negative influence from the Portuguese. By the time, the Lisbon Inquisitor

had arrived; many moral irregularities were taking place in Brazil[iv]. Thus,

the Lisbon Inquisitor’s presence tipped the scale in favor of the Jesuits and

the other missionary orders.

Tomacuana had gotten in trouble with the Inquisition

because of his go between methods. His actions did not promote the Evangelization

of the Indians. Rather, they helped perpetuate their heretical practices. For

the Jesuits, men like Tomacuana also helped perpetuate the illegal enslavement

of the Indians[v].

Plus, the fact that Tomacuana engaged in

pagan rituals was unacceptable[vi].

In Metcaft “Power”

reading, the Lisbon Inquisitor wrote a decree that punished those who lived

sinful lives. Those that confessed their sins and the sins of people they knew

got to keep their estates[vii].

What was considered sinful was any

practice or behavior that did not match the mores of a Catholic Portuguese

country. Naturally, someone like Tomacuana became a target under this decree. Many

of those that confessed implicated Fernandes Nobre as a follower of the

heretical “Santidade” Indian religion. His wife too accused him of tattooing

himself. Thus, the charges brought against Fernandes Nobre had nothing to do

with his line of work. Rather, the methods that he used to obtain slave labor

were seen as sinful by society.

Based on the list of sins posted by the Lisbon

Inquisitor, it seems that Fernandes Nobre was guilty of adopting Indigenous

practices while living in the Colony[viii].

Metcalf believes that the Jesuits

convinced the Inquisition of making this a sin in order to get rid of the “mamelucos”

like Fernandes Nobre[ix].

The mamelucos were half native, half Portuguese. Their native mothers had

taught their language and culture. They had the advantage of being able to live

in both the Native and Portuguese world. The way they worked was very similar

to the Jesuits. Both became fully integrated into an Indian clan. The Jesuits

too learned the language and culture of the Natives. However, their aim was to

establish missions. The mamelucos, on the other hand, manipulated the Indians

into getting other Indian slaves for the sugar planters.

Obviously, these mamelucos interfered with the Jesuit

missions. It was noted that many of the denunciations against the mamelucos

where put forth by Jesuit priest[x]. They saw their opportunity to get rid of

their competition with the arrival of the Lisbon Inquisitor. By getting rid of

them, the sugar planters would lose their means of obtaining Indian slave

workers. In Metcalf “Domingos Fernandes Nobre”, shows how mamelucos obtained

Indian labor for the planters. Aside from knowing the languages and culture,

Fernandes Nobre had tattooed himself. In doing so, he showed the Indians he was

a brave warrior. This earned him the nickname Tomacuana. By earning their

trust, Fernandes Nobre traded weapons for slaves[xi]. These slaves were usually people from enemy

tribes.

In his last mission, Fernandes Nobre was dealing with a

tribe whose worship was called “Santidades”. This sect was seen dangerous because

it predicted the coming of a being who would free all under the yoke of

oppression. This naturally appealed to a lot of slaves. Many escaped to join

the “Santidade” group[xii].

Thus, it did not bode well for Fernandes Nobre to participate in a sect that was

both heretical and that caused slaves to escape their masters. Another problem

was that Santidade also drew in a large following of mamelucos. It makes sense

that those who followed Fernandes Nobre wondered if he truly believed in the

rituals of the Santidade. These suspicions were due to Fernandes Nobre’s

mamelucos heritage. For this reason, many who accused Fernandes Nobre to the

Inquisition had been part of his expeditions to the Santidade[xiii].

In the end, all these accusations were only a means to an

end. Fernandes Nobre could only obtain forgiveness by foregoing all of his

Native practices. He had to assimilate completely into the Portuguese society[xiv].

With this forced assimilation, Fernandes

Nobre lost his ability to serve as a go between. He could no longer gain the

confidence of the Natives like before. Thus, via this method, the Jesuits made

it harder for the mamelucos to excerpt their influence over the natives. Seeing

the attention given to the mamelucos, it is obvious that they had great power

in the colony. They alone made things harder for the Jesuits to advance their

colonization model. The only way for the church to combat them was to make a sin

the methods the mamelucos employed in their line of work. The visit of the

Lisbon Inquisitor gave the Jesuits the chance they needed to get rid of their

competition.

[i]

Alida C. Metcalf, “Domingos Fernandes Nobre” Pg 52

[ii]

Alida C. Metcalf, “Power” Pg 2

[iii]

Metcaft, “Power” Pg 4 or Pg 239

[iv]

Metcaft, “Domingos Fernandez Nobre” pg 60

[v]

Metcaft, “Power” Pg 3

[vi]

Metcaft, “Domingos Fernandez Nobre” pg 60

[vii]

Metcaft, “Power” Pg 4 or Pg 239

[viii]

Metcaft, “Power” Pg 4 or Pg 239

[ix]

Metcaft, “Power” Pg 241

[x]

Metcaft, “Power” Pg 241

[xi]

Metcaft, “Domingos Fernandez Nobre” pg 55

[xii]

Metcaft, “Domingos Fernandez Nobre” pg 57

[xiii]

Metcaft, “Domingos Fernandez Nobre” pg 56

+Colonial+Brazil+depiction+of+the+Natives+eating+a+misionary.jpg)